Burial Culture and Haniwa

The Kofun period was a time when the burial culture rapidly permeated society, marked by the construction of kofun (ancient burial mounds) to enshrine emperors and nobles of the Yamato regime. Up until the mid-Kofun period, vertical stone chambers were used as burial rooms within the mounds, while later periods saw a shift towards horizontal stone chambers, which were more suited for family burials and allowed for subsequent interments. Horizontal stone chambers, as described in the “Kojiki” through the myth of Izanagi and Izanami, embody a structure connecting this world with the afterlife. The grave goods varied over time; religious items were common in the early period, while practical items like weapons and horse gear became prevalent in the later periods.

Haniwa, clay figures produced during the Kofun period and placed around or on top of the burial mounds, are indispensable when discussing the burial goods of this era. Starting from simple cylindrical shapes, haniwa evolved into a variety of forms, including human figures, houses, weapons, and animals, offering valuable insights into the religious beliefs, afterlife views, societal structure, and culture of ancient Japan.

Haniwa can be broadly categorized into uncolored cylindrical haniwa and figurative haniwa, which include models of humans, animals, and houses. The cylindrical haniwa were often arranged in rows around the tombs, serving as boundary markers, while the figurative haniwa, appearing mainly from the mid-Kofun period onwards, reflected the deceased’s social status, occupation, daily life, and beliefs.

(Image citation: ライフハックアナライザー)

Yamato Regime and National Unification

The proliferation of kofun was a demonstration of power by the Yamato regime, which unified Japan for the first time. Let’s delve into what kind of regime the Yamato was.

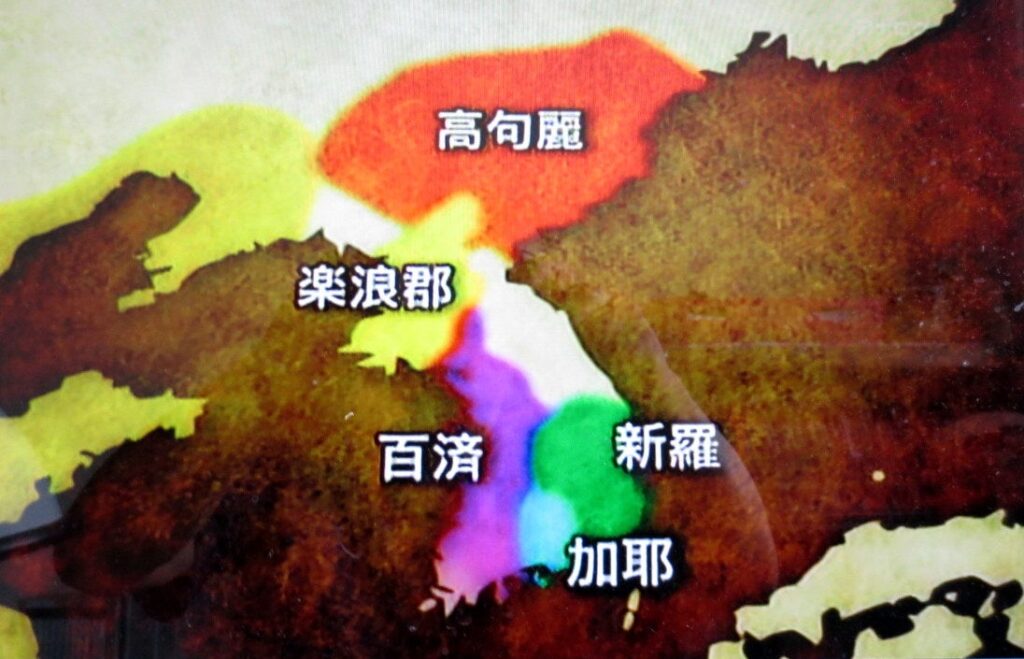

Following the decline of the Yayoi period’s Yamatai Kingdom, which prospered through interactions with China’s Later Han and Wei dynasties but waned after the death of Queen Himiko, various regions such as Kibi, Izumo, and the Kinai area rose in power. Ultimately, the Kinai-based Yamato regime emerged as the predominant force, leading to its governance over Japan. The leaders of this regime were called “Ōkimi” (great kings), supported by Kinai executives and regional aristocrats, establishing a clear hierarchical structure.

However, the details surrounding the birth of the Yamato sovereignty fall into the “Blank Fourth Century,” with reliable records only available from the 5th century onwards. The main sources of information for this period are the “Kojiki” and the “Nihon Shoki,” with the latter detailing the reign of Emperor Sujin, the 10th emperor, who is credited with strengthening the Yamato sovereignty. During his reign, Japan’s first census was conducted, levies were imposed, irrigation ponds were expanded, ships were built, and four generals were sent to various regions, facilitating diplomacy and territorial expansion. These policies allowed the Yamato sovereignty to transcend local kingdoms and evolve into a centralized authority, symbolized by the construction of large kofun.

The Yamato regime integrated the ritualistic culture from the Yayoi period into court ceremonies, governing people through a reverence for the divine. In the early Kofun period, invasions into other territories were justified in the name of spreading the correct faith as dictated by the gods. However, as the power of local chieftains grew in the later Kofun period, the Yamato regime shifted from relying solely on divine authority to institutional governance. This involved appointing ministers and high-ranking officials to govern the state, establishing regional governors (Kokushi), and forming skilled groups known as Be. The establishment of the Kabane system aimed to maintain social hierarchy, prevent rebellions, and facilitate governance. Through these adaptive strategies, the Yamato regime continued its rule over Japan.