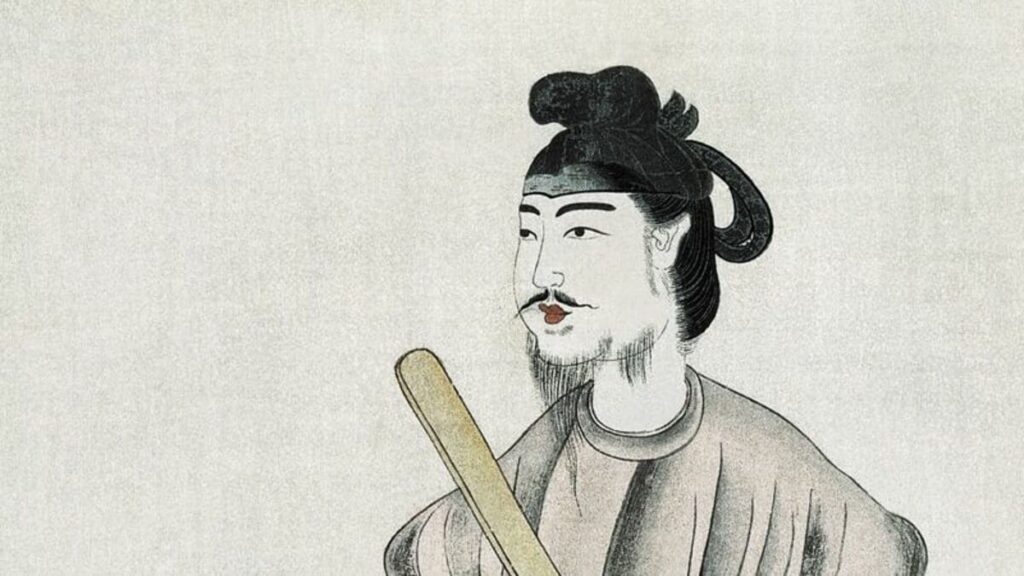

The Asuka period, known for the remarkable Prince Shōtoku, is a significant era in Japanese history, marked by various legends surrounding this iconic figure, including his ability to understand ten conversations simultaneously. This period saw the emergence of major political shifts and the foundational steps towards establishing a centralized state governed by a codified system of laws. Let’s delve into the events that characterized the Asuka period.

The Dawn of the Asuka Period

The Asuka period commenced in the latter half of the 6th century and extended into the 7th century. During this time, the Soga clan, a powerful aristocratic family, began to rise in prominence. Influenced by immigrants, the Soga clan embraced Buddhism, leading to a power struggle with the Mononobe clan, who were opposed to the new religion. The conflict culminated in the defeat of the Mononobe clan by Soga no Umako, solidifying the Soga family’s political dominance.

However, as the Soga clan’s power and tyranny grew, there was a pressing need for a new political order. It was within this context that Prince Shōtoku emerged as a pivotal figure. Serving as regent to Empress Suiko, Prince Shōtoku embarked on the journey of building a centralized state. Deeply influenced by Chinese political thought, he incorporated Buddhist and Confucian ideals into his governance, positioning himself as the de facto ruler and central figure in the nation’s administration.

Prince Shōtoku’s policies and leadership significantly transformed Japan’s political landscape, laying the groundwork for the Asuka period. His era witnessed the establishment of the Seventeen-Article Constitution, the dispatch of emissaries to the Sui Dynasty in China (known as Kenzushi), and the flourishing of Asuka culture. These events were instrumental in shaping the characteristics of the Asuka period and laid the foundations for Japan’s ancient culture and political system, which would influence subsequent eras such as the Nara and Heian periods.

Through his visionary leadership and innovative policies, Prince Shōtoku played a crucial role in steering Japan towards a centralized and orderly state, marking the Asuka period as a transformative chapter in the annals of Japanese history.

The Achievements of Prince Shōtoku

Prince Shōtoku, hailed as a prodigy from childhood, leveraged his talents to effectively organize the government. This article highlights several policies implemented by Prince Shōtoku.

(Image citation: 東洋経済)

Establishment of the Twelve Level Cap and Rank System

In 603, Prince Shōtoku created Japan’s first official rank system, known as the Twelve Level Cap and Rank System. This system aimed to select officials based on their abilities and achievements, contributing to the construction of a centralized state centered around the emperor. It replaced the traditional clan system, emphasizing individual merit over family lineage or name. The system categorized status into twelve levels, indicated by the color of one’s cap, promoting equality and fair assessment of talent within society. The introduction of this system reflected Prince Shōtoku’s progressive political ideals and brought significant transformation to Japan’s political structure.

The Seventeen-Article Constitution

In 604, Prince Shōtoku established the Seventeen-Article Constitution, Japan’s first moral and political code. Unlike modern constitutions, this was more a set of ethical guidelines aimed at officials in the imperial court, rather than absolute laws. It included principles such as valuing harmony and respect among officials and emphasized the importance of adhering to Buddhist teachings and absolute obedience to the emperor’s commands. The establishment of this constitution aimed to solidify order within the court and strengthen governance. The creation of the Seventeen-Article Constitution marked a transitional period in Japanese political structure, symbolizing a shift from “Great King” to “Emperor” and reflecting Prince Shōtoku’s political philosophy and his commitment to a centralized government system.

The Dispatch of Envoys to Sui China

In 607, aiming for equal diplomatic relations, Prince Shōtoku sent Ono no Imoko as an envoy to the Sui Dynasty in China. This move was intended to demonstrate Japan’s stance on engaging in diplomacy as an equal with the Sui, which adhered to the Sinocentric world order. Prince Shōtoku equipped Ono no Imoko with a letter for the Sui emperor, boldly stating, “The Son of Heaven in the land where the sun rises sends this to the Son of Heaven in the land where the sun sets.” Despite the Sui Emperor Yang’s initial perception of this as impertinent, the political context of the time led to a peaceful maintenance of relations between the two nations. This mission is noted as a successful example of Prince Shōtoku’s equal-footing diplomacy and played a crucial role in establishing Japan’s international standing.

Asuka Culture and Horyuji Temple

The Asuka culture, which flourished in Japan during the Asuka period from the late 6th to the 7th century, was a cosmopolitan culture rich in international influences. This era saw the introduction of Buddhism to Japan from China, along with a variety of cultural elements from India, Greece, Persia, and other foreign lands. The fusion of these cultures led to the creation of unique Japanese art and architectural styles, forming the foundation of Asuka culture. Characterized by its religious centrality around Buddhism and the amalgamation of diverse technological and artistic styles, this period’s Buddhist art includes statues and murals often reflecting influences from Indian and Central Asian styles. Architecturally, the period is noted for its Chinese-influenced temple constructions and the advanced development of wooden architecture.

One of the quintessential representations of Asuka culture is Horyuji Temple. Known as the world’s oldest surviving wooden structure, Horyuji was established in 607 under the auspices of Prince Shotoku. The temple vividly reflects the architectural techniques and artistic elements introduced to Japan with the advent of Buddhism, with its Golden Hall and Five-Story Pagoda standing as precious conveyors of the essence of Asuka culture. The Shaka Triad housed in the Golden Hall, considered a masterpiece of Asuka-period Buddhist art, showcases not only the deep spirituality of Buddhism but also the high level of technical and artistic achievement of the time.

The Asuka culture symbolizes the period when Japan first embraced foreign cultures on a large scale and developed them into a unique form of its own. Horyuji Temple serves as one of the most prominent examples of this era, cherished and studied by many as an essential heritage in Japanese history and culture.

(Image citation: MYSTAYS)

The Taika Reform

Despite Prince Shotoku’s adept political maneuvers, he passed away due to illness in 622. This led to the resurgence of the Soga clan, previously restrained by Prince Shotoku. Within the Soga, particularly influential were Soga no Iruka and Soga no Emishi, who, possibly resenting their suppression under Prince Shotoku, went so far as to eliminate the entire family of Prince Shotoku’s son, Yamashiro no Oe no Ou, becoming untouchable forces within the court. It was Prince Nakano Oe and Nakatomi Kamatari who sought to change this dire situation.

Engaging in secret discussions while playing kemari, Prince Nakano Oe and Nakatomi Kamatari plotted to eliminate the Soga clan from political power. Utilizing a false imperial order for a ceremonial event to lure Soga no Iruka into a vulnerable position, Prince Nakano Oe personally assassinated him, leading to the cornered Soga no Emishi’s forced suicide. This series of events is known as the Taika Reform.

The Taika Reform marked the end of the Soga clan’s power and significantly transformed the political landscape. Following this, Prince Nakano Oe and Nakatomi Kamatari implemented a series of political, social, and economic reforms, transitioning Japan from a clan-based political system of the Kofun period to a centralized state system centered around the emperor.

Policies Post-Taika Reform

Following the Taika Reform, the new government led by Prince Nakano Oe established Japan’s first era name, “Taika,” and moved the capital from Asuka to Naniwa (now Osaka). The reform aimed at establishing a centralized national system and implemented key policies including:

The Public Land and Population System: Asserting that land and people were the property of the state, not private possessions of clans, thereby strengthening the authority of the state centered around the emperor. The Equal-Field System: Based on household registration, adult males were allocated land (known as kubunden) which was to be periodically redistributed, with a portion of the harvest due as a tax to the state. The Taxation System of Soyocho: Reforming the tax system to require a certain percentage of the harvest as a tax, along with textiles and specialty goods as labor dues, and items like silk and thread as additional levies. These systems were inspired by the Chinese ritsuryo system. The Provincial and District System: Japan was divided into provinces, districts, and villages, each with its appointed leaders, establishing the administrative foundation for a centralized governance system. These policies significantly advanced the establishment of a centralized state and the modernization of governance in Japan. The Taika Reform represented a pivotal shift in Japanese politics, society, and economy, deeply influencing Japan’s subsequent development.

Battle of Baekgang

The Asuka period in Japan was marked not only by domestic reforms but also by significant changes in foreign relations. During this time, the Tang dynasty, which had gained power in China and subjugated Silla, launched a military invasion against Baekje, which had close ties with Japan. To rescue Baekje, Emperor Saimei decided to dispatch troops to the Korean Peninsula, leading to the Battle of Baekgang, Japan’s first military conflict with a foreign power.

The Japanese forces, led by Prince Naka no Ōe, faced a severe defeat against the combined forces of Tang and Silla, largely due to strategic disadvantages and adverse natural conditions. Fearing Tang’s expanding power after this defeat, Prince Naka no Ōe returned to Japan and ascended to the throne as Emperor Tenji, initiating various measures to fortify the nation.

To prepare for potential invasions by Tang, Emperor Tenji implemented defense strategies such as creating a national census called the “Kōgo-nenjaku” and constructing water fortresses along the coast of Kyushu, staffing them with soldiers. He also relocated the capital to Omi-Otsu Palace, a natural fortress in Omi, to strengthen the country’s defense.

Ultimately, the invasion from Tang and Silla never materialized due to deteriorating relations between them, leading to conflicts. However, the defeat at Baekgang heightened Japan’s national defense awareness, paving the way for the implementation of various protective measures.

(Image citation: Japaaan magazine)

Jinshin War

Following the era of significant reforms and defense strategies under Emperor Tenji, a succession dispute erupted regarding who would next ascend to the throne. Emperor Tenji preferred his son, Prince Ōtomo, but according to traditional succession rules, his brother, Prince Ōama, was the rightful heir. Amidst this turmoil, Prince Ōama, to ensure his safety, declined the throne and secluded himself in Yoshino, Nara.

Upon Emperor Tenji’s death, efforts to exclude Prince Ōama from the throne intensified within the court. To counteract, Prince Ōama rallied support from regional clans and raised an army, leading to the conflict known as the Jinshin War. This civil strife concluded with an overwhelming victory for Prince Ōama, forcing Prince Ōtomo to commit suicide.

Prince Ōama then ascended to the throne as Emperor Tenmu, establishing a government dominated by the imperial family and further centralizing political structures. The Jinshin War eliminated significant opposition to Emperor Tenmu, compelling regional clans to submit to imperial authority.

Taihō Ritsuryo

Continuing the reforms initiated during the Great Reform, Emperor Tenmu adopted the Tang dynasty’s administrative and penal systems, introducing the Ritsuryō system to Japan. After Emperor Tenmu’s death, his wife, Empress Jitō, succeeded him, moving the capital to Fujiwara-kyō, which is present-day Kashihara and Asuka in Nara Prefecture. Fujiwara-kyō, designed with a grid layout inspired by Chang’an, the Tang capital, became Japan’s first full-fledged capital city.

In 701, under the leadership of Prince Osakabe, Japan enacted its first comprehensive national legal code, the Taihō Ritsuryo. This landmark event signified Japan’s transformation into a Ritsuryō state. The Ritsuryō system, composed of the “Ritsu” (penal codes) and “Ryō” (administrative regulations), aimed to organize the nation’s laws and administrative structures systematically.