The Yayoi period marks a significant turning point in Japanese history with the introduction of rice cultivation. This transition from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to one centered around rice farming brought about profound changes in diet, enabled the stable storage of food, led to disparities in wealth, and resulted in increased conflict. The Yayoi period is also often associated with the enigmatic Himiko of the Yamatai Kingdom, known for its trade with China and the reception of a gold seal.

Introduction of Rice Cultivation

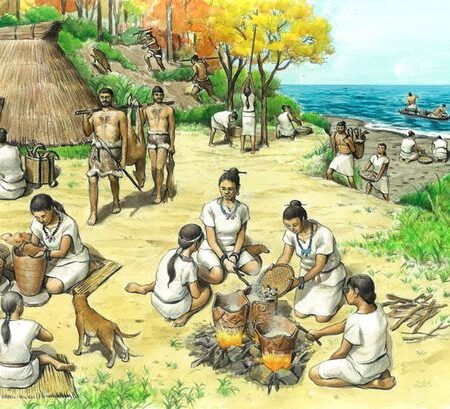

The most transformative event of the Yayoi period in Japan was the introduction of rice cultivation techniques from the Korean Peninsula and mainland China. This shift from hunting, gathering, and slash-and-burn agriculture to wet rice farming using paddy fields facilitated a move towards sedentary village life. The labor-intensive and managed nature of rice farming necessitated more organized community living, significantly altering the social fabric of Yayoi settlements.

Lifestyle Changes in the Yayoi Period

The advent of rice cultivation had a profound impact on the lives of the Yayoi people, affecting everything from dietary habits to the development of settlements and conflicts.

The Staple Diet of Rice

With the spread of rice cultivation, rice became the staple food of the Yayoi people. Its high nutritional value and storability made it an invaluable resource for stable food supply, supporting population growth and societal development. Regular harvests ensured a consistent food supply, contributing to social stability.

Adoption of Farming Tools

The introduction of rice cultivation necessitated the development and use of efficient farming tools. Tools such as hoes and sickles for plowing and harvesting rice, as well as mortars and pestles for threshing, became widespread, streamlining the tasks of tilling, planting, and reaping. The durability and efficiency of iron agricultural tools, in particular, significantly enhanced work speed and productivity. These technological advancements played a crucial role in increasing productivity and stabilizing food supply, laying the groundwork for population growth and social advancement.

(Image citation: 弥生ミュージアム)

Yayoi Pottery

Yayoi pottery, produced during this era, exhibits significant differences in manufacturing techniques and shapes compared to the preceding Jomon pottery, reflecting the new lifestyle ushered in by rice cultivation. The use of the potter’s wheel allowed for the production of uniform, thinner, and larger pottery pieces, facilitating mass production essential for the Yayoi people’s daily lives. Yayoi pottery varied in shape according to its use, with wider and shallower pots for cooking and food storage, making them more suitable for boiling and steaming. With the spread of rice cultivation, large steamers for rice were also developed. Ritual pottery often featured decorations and was used in ceremonies and festivals, indicating a spiritual or ceremonial aspect to their use.(Image citation: 本庄早稲田の杜ミュージアム)

The Emergence of Raised Floor Storehouses

As stable food supply became possible through rice cultivation, new challenges in the storage of harvested crops emerged, leading to the introduction of raised floor storehouses. These structures were designed with elevated floors to protect grains from moisture and pests, enabling long-term storage of harvests. The widespread use of raised floor storehouses laid the foundation for a stable year-round food supply.

Importation of Iron and Bronze and Ritual Practices

During the Yayoi period, iron and bronze began to be imported from the Korean Peninsula and China, and these metals were used not only for agricultural tools and weapons but also for ritual objects. Bronze mirrors and bronze bells, in particular, played an important role in ceremonies and rituals, symbolizing the status of rulers or communities. The use of these ritual objects indicates the development of the society’s religious aspects and cultural spirituality.

(Image citation: 国立歴史民俗博物館)

Emergence of Wealth Disparities

The spread of rice cultivation led to increased prosperity for groups or regions with high production, who gained more influence in society. Conversely, groups or regions lacking technology or suitable land for rice cultivation were less productive and economically disadvantaged. Such economic disparities promoted social stratification, making wealth differences more pronounced. These disparities became a source of competition and conflict among groups, contributing to social tensions.

Increase in Conflicts

As wealth disparities widened, conflicts over resources and power increased. Disputes often centered around valuable resources like rice and iron, leading to the amalgamation of smaller communities into larger settlements or states by those with abundant resources. Archaeological sites from this period reveal the presence of powerful individuals buried with lavish grave goods, suggesting that these elites governed their regions.

The Beginning of Burial Culture

The Yayoi period saw the development of burial cultures reflecting the status of individuals or groups. There was a diversification in burial practices, with powerful figures or important individuals being buried in large tombs accompanied by luxurious grave goods. These burial customs reflect beliefs about the afterlife and the relationship between the living and the dead, indicating changes in social hierarchies and values.

(Image citation: good Luck Trip)

Yamatai Kingdom

The Yamatai Kingdom, existing in the 3rd century in Japan, remains a subject of various theories regarding its existence, with many scholars speculating its location in the Kyushu region. Described in the “Wei Zhi” (Records of Wei) of the Chinese chronicles, Yamatai was considered one of the most powerful entities among the numerous states in the Japanese archipelago at the time. According to the “Wei Zhi,” the kingdom was ruled by Queen Himiko, who possessed sacred authority and was skilled in divination.

Himiko and Tribute

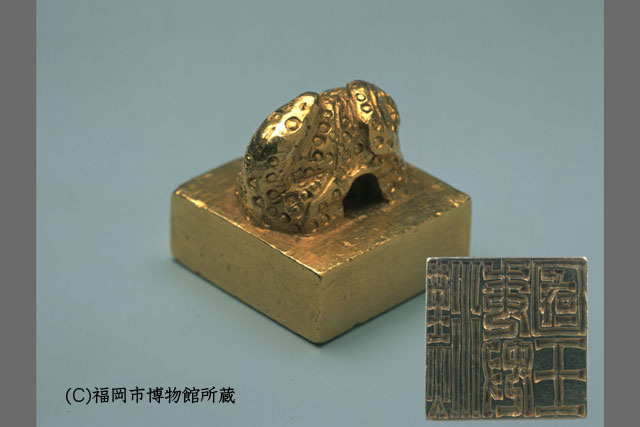

As the queen of Yamatai, Himiko actively engaged in diplomatic relations, notably with the later Han and Wei dynasties of China. In the mid-3rd century, Himiko sent envoys to Wei, proclaiming herself as the “Queen of Wa in friendship with Wei,” offering tribute. In response, the Wei emperor recognized her title, bestowing valuable gifts such as a golden seal and purple ribbons. This golden seal, in particular, elevated the status of Yamatai and symbolized the authority of Himiko and her kingdom.

Discovery of the Golden Seal

The golden seal, inscribed with “King of Na of Wa in Han Dynasty” found on Shikanoshima Island in Fukuoka Prefecture in 1784, is believed to match the one given to Himiko by Wei, serving as a crucial archaeological evidence for the existence of Yamatai.

(Image citation: 弥生ミュージアム)

Location of Yamatai

The exact location of Yamatai has been a long-standing debate in historical and archaeological circles. While the Kyushu theory is prevalent, some argue for its location in the Kinki region, with no consensus reached within the academic community. The kingdom, under Himiko’s rule, likely served as a political and cultural hub during the Yayoi period, with its influence extending over a wide area.

Yoshinogari Site

The Yoshinogari site, located in Saga Prefecture on Kyushu Island, is a significant Yayoi period archaeological site, thriving from the 3rd century BC to the 3rd century AD. Its scale and preservation make it crucial for understanding ancient Japanese history.

(Image citation: 吉野ヶ里公園)

Features of the Site Moats and Earthen Walls: The site’s most notable features include extensive moats and earthen walls, spanning about 3 kilometers, likely serving for defense and demarcating settlement boundaries. Residential Remains: Numerous pit dwellings found at the site offer insights into the living conditions and lifestyles of the time, shedding light on the daily lives and social structures of the Yayoi people. Rice Paddy Fields: Rice paddy fields in the vicinity indicate the practice of rice cultivation, highlighting the economic foundation of the local community and the advanced agricultural techniques of the period. Workshops: Evidence of iron and pottery workshops suggests the production capabilities and trade activities of the time.

The end of the Yayoi Period

The Yayoi period, marked by the introduction of wet-rice farming by immigrants, saw widening economic disparities and increasing conflicts between settlements. This era was characterized by strong regional identities within settlements, which gradually merged or dissolved due to conflicts, leading to the emergence of regional chieftains. These developments, marked by the construction of large-scale burial mounds to honor these chieftains, transitioned the era from the Yayoi to the Kofun period.